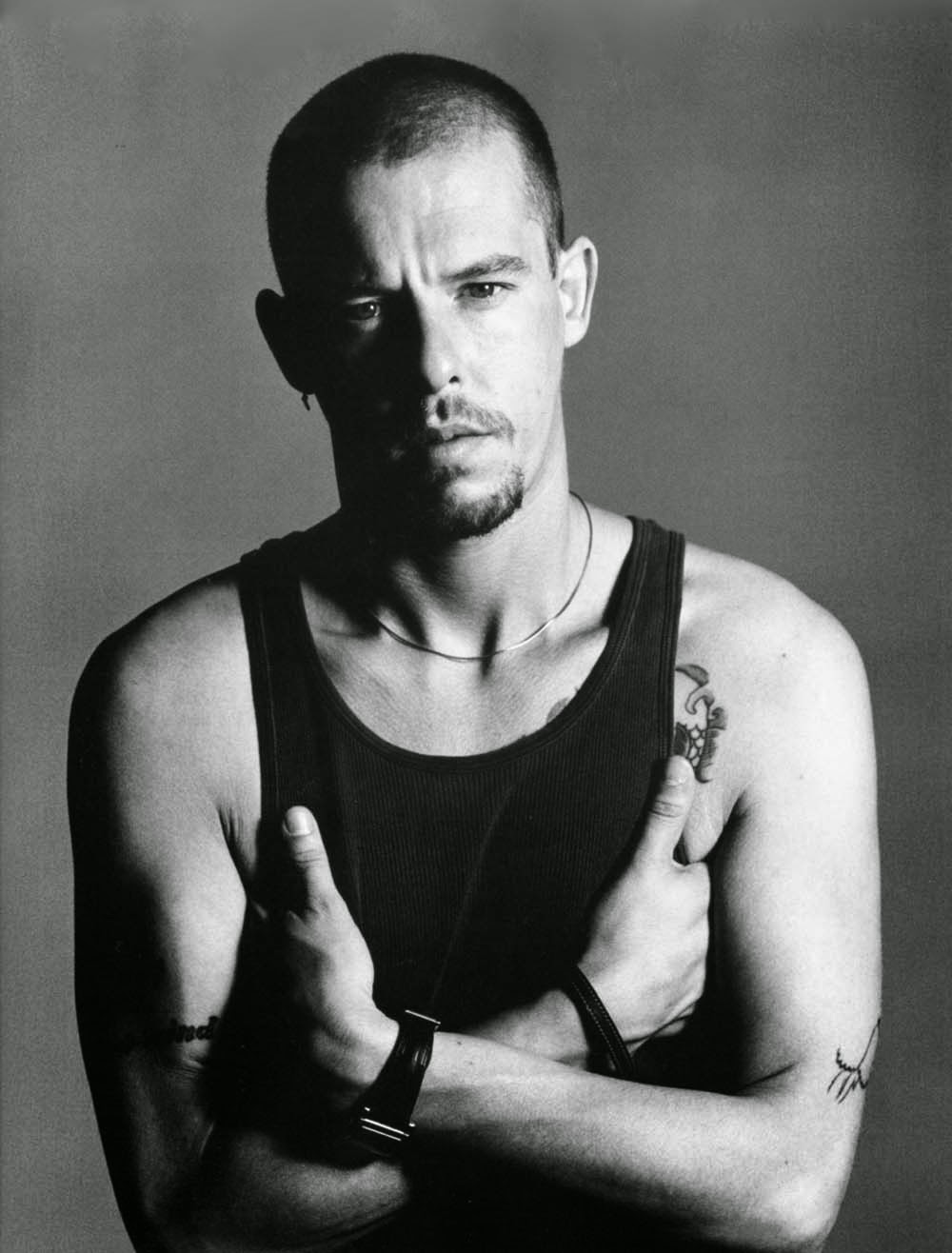

Alexander McQueen: Blood Beneath the Skin

Things kicked off about a week ago with the V&A Museum’s

recreation of Savage Beauty* an

exhibition on McQueen originally displayed at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of

Art back in 2011. Its great success

prompted a (rather late) sequel in London, wholly pervasive in its

advertisement on the doors of our cabs, and the walls of our tube

stations. Literature on McQueen has also

expanded substantially over the last few years, though in this case it proves

more difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff.

One of the most compelling reasons to read a book such as

this is the fact that it intertwines the designer’s work life and personal

life. Wilson uses this to great effect,

managing to cover all of the major events in McQueen’s personal and work life,

while also bringing more obscure anecdotes to the table, stemming from personal

conversations and interviews the author conducted with McQueen’s family and

friends. This alone inherently elevates

this book above the competition, but there are of course, yet more positive

aspects. My only personal lamentation is

that it is written after the death of Isabella Blow, meaning she was unable to

give comment. Similarly, it does not

make use of those close to her, such as milliner Philip Treacy, restricting

itself to Detmar, her husband.

Along with his experiences of a child, Wilson documents

McQueen’s extensive drug use, and reveals shockingly that he knew he was HIV

positive, yet elected to continue having unprotected sex, despite making

charitable donations to various AIDS organisations. Never shying away from controversy, the book

also claims that shortly before his suicide, that he was going to

design his last collection then commit suicide during the show by placing

himself inside a Perspex or glass box and shooting himself in front of the

audience. This debauched lens through

which McQueen’s life and career are viewed either detract or add to the value

of the book, depending entirely on what the reader seeks to gain. Those who know little about McQueen as a

designer are not really the audience for this book, it is for those who wish to

gain an intimate insight into McQueen’s life, and the trials and tribulations

it brought about. It serves as a beneficial companion to Savage Beauty, written to induce from us a heavy suspiration upon

the realization that the fashion industry destroyed one of its own brightest

talents.

What, then, can we gain from this book? For one, we may take away the understanding

that fashion is not frivolous, rather that it is largely engrossing, capable of

arousing strong emotions when executed by such an iconic designer. McQueen was one of the few creatives who was

not fazed by the money, and created clothing that made women feel beautiful and

strong, uxoriously thanking women, whom he claimed to be the true heroes in his

life. The British do love an underdog, especially one who went from having

nothing to owning a £20m brand, and perhaps that is what this book’s appeal

lies in.

Blood Beneath

the Skin depicts McQueen as he was, a genius who was indeed

reprehensible at times, but a tortured soul, who deserves our sympathy and

gratitude for all he gave over the years, and for all he lost. The sole regret one could have upon reading

this is that, given this book was written with the approval of the McQueen

family, we may well never know the true extent of the horrors that bedeviled

Lee McQueen’s personal life.

Nevertheless, this book is an unflinching but wonderfully-readable

account, backed up by fantastic research. Indeed, as McQueen’s sister claimed, this is

the biography Lee would have wanted.

Christian Robinson

*Weirdly, 600 copies of Blood

Beneath the Skin were ordered by the V&A to accompany Savage Beauty, but two weeks before the

exhibition opened, the publishers were told that the museum had been asked not

to stock any biographies. The V&A

have made clear that they do not wish to make known the less-glamorous aspects

of McQueen’s life, much to the consternation of Andrew Wilson.

Comments

Post a Comment